This book appealed to several of us here but we weren't able to review it so I decided we'd feature it. There's a short Q&A with the author, Jackie Copleton, some Japanese recipes (including cake!), and the publisher is giving away one copy of the book to a US reader. Make yourself comfy and enjoy!

Jackie Copleton spent three years teaching English in Nagasaki and Sapporo. A journalist, she now lives with her husband in Glasgow, Scotland.

Find Jackie Online:

website

goodreads

What sparked your interest in a story set in Nagasaki? Of the two cities targeted by the atomic bombs, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, why did you choose Nagasaki?

I’m going to have to take you back to 1993. I was 21 years old. I’d graduated from university with a degree in English and had no idea about what I wanted to do in terms of a career. As I trawled job advertisements at my parents’ home, a friend who was working at a school in Japan wrote out of the blue: “Come here. You’d love it. You can teach.”

In that weird synchronicity of life, an advert appeared in a newspaper looking for graduates to apply to GEOS, at that time one of the world’s biggest English language schools. I got the job and was allocated, at random, the city where I’d be teaching: Nagasaki. Fate, I guess, or luck, led me there. I loved my own small piece of Nagasaki: the curious ramshackle home I rented with the hole in the floor in lieu of a flushing toilet, the tatami mats and paper sliding doors in the bedroom, the tailless cats that loitered on my doorstep, the lack of street names that left me lost on my first night, the temples and shrines and foreigner cemeteries, the food, and the sheer adventure of being dropped into a world so alien I had my own “alien registration” card.

I knew I wanted to set my first book in Nagasaki but I was wary about tackling the atomic bomb. It was too big a topic, the devastation real and not imagined, the aftermath still felt by generations of families. However, every time I wrote about the city, the plot—or rather the characters—took me back to the Second World War. And so reluctantly, and cautiously, I began to feel my way towards a story about an elderly woman called Amaterasu Takahashi who had lost her daughter and grandson when Bockscar dropped Fat Man over Nagasaki—and who had lived with that loss for forty years.

During my two years living in Nagasaki, I attended the 50th anniversary of the atomic bomb at Nagasaki Peace Park, alongside 30,000 more people who gathered together in the stifling heat to remember the dead. I watched a small boy eat ice cream by a fountain built to commemorate the fatally injured who had cried out for water. I stored the memory of that boy away and later he turned into Hideo Watanabe, the seven-year-old child seemingly killed on August 9, 1945.

Decades pass in the book, and a man going by the same name arrives on the doorstep of Amaterasu’s home in the US to declare he is the grandson she thought dead. The adult Hideo has a type of retrograde amnesia and I wanted his condition to reflect a certain historical amnesia that we have in the West with regards to the atomic bombs. Nagasaki was the second city hit. When we talk about nuclear war Hiroshima is more often cited. That’s quite a thing, to have second billing but to have shared the same horror.

Beyond inspiring my first novel, Nagasaki has had a huge impact on my life. It gave me my first job as a teacher, later my profession as a journalist—and wonderful memories.

On my first night in the city, a sushi restaurant owner, who also happened to be a former boxer, declared: “For as long as you live in Nagasaki I will protect you.” I feel the book is my way of repaying my debt to all the kind people who looked after me when I lived there. They protected me when I was young and a long way from home.

Family and relationships are central to this novel, especially the secrets we keep and the question of how well we can ever know those closest to us. Why did you choose to explore the history of Nagasaki’s bombing through the lens of family?

The statistics are hard to verify, people were on the move, the war was chaotic, so we will never know how many people in total died in Nagasaki because of the bomb, but one estimate is 75,000, with half of that number killed on the day. How can one person, one reader, one writer assimilate, comprehend and articulate that loss? The number is too big. So step back, and take another step back and another until you are left with just one family and one single perspective: Ama, a survivor, a hibakusha.

I wanted to imagine what happens when personal and public history collide. Ama’s relationship with the bomb is more complicated than just being a victim. She believes herself responsible for her daughter and grandson’s deaths. She feels her actions, her flaws, her determination to try to control the world around her—and those she loves—is the reason they are killed. She drove them to Urakami, the epicenter. When we meet Ama, in her early 80s, she is still carrying this guilt. Why should she get to live when those closest to her die? This is her torment.

I wanted to explore what happens when our own “small” lives—the secrets we keep, the harm we try not to do but do, the compromises we cannot bear to make—are overshadowed by one bigger moment that defines us for the rest of our lives. The bomb is the physical force that destroys Ama’s family, but she is also an emotional force that causes untold damage, she thinks. People feel sorry for her because of the former and she hates herself for the latter.

Ama lives with her failings every day until a man who claims to be her grandson begins to suggest she can forgive herself, that regret and guilt are not necessarily the end of her own story. That maybe she can allow herself a happier ending.

A DICTIONARY OF MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING is set both in more recent history in the United States and, through flashbacks, Japan in the first half of the 20th century. How did you decide to structure the novel this way?

Memory isn’t linear so why does story-telling need to be? Our past, present and future are all gloriously, irrevocably, and sometimes terribly linked.

My own family history probably also played a part in the structure of the novel. My maternal granddad was killed in Normandy, France on August 5, 1944 and my paternal grandfather fought against the Japanese in Burma, but died before I was born. These men are strangers and yet their legacy lives on through their offspring. My mother will never stop mourning a father she never knew. Two slices of history collide and run parallel: the living cohabit with the dead. How are our lives shaped, or lessened, by such as loss and how can we understand our selves fully if there are these missing chunks in our past?

I will confess I didn’t appreciate how tricky the split-time narrative would be. I had endless notes to check that the births, deaths, and marriages aligned. Chapters were shuffled back and forward, others were erased, historical dates had to be slotted in and then worried over. Despite the challenge of weaving the two timeframes, I loved how it helped drive the plot forward, showing why Ama’s present is a product of her past but also how she might carve out a different future.

You bring Amaterasu to life so vividly on the page. Was it challenging to inhabit a character whose time and culture are so different from your own?

Yes. In fact for a long time I wanted my main character to be a Western woman, so that I had a point of reference: me. But I wasn’t hugely interested in writing my story! And the joy of writing is the freedom it allows you to inhabit other lives, cultures, and genders. Luckily I also had three women who inspired Amaterasu.

When I lived in Nagasaki, my landlord was an elderly lady, elegant and sprightly despite her age, who lived in the house next to mine with her disabled husband. We would take tea together whenever I paid the rent and amiably sit together and laugh away at conversations neither of us understood as my Japanese was poor and her English non-existent. Despite our inability to communicate her personality shone through. The twinkle in her eyes suggested a rich life lived beyond her final role as a carer for her husband.

A few years ago I was also privileged to meet a woman of the Baha’i faith who had fled Iran 35 years ago when the Khomeini regime came to power. Her daughter, a young beautiful university graduate, stayed behind and was killed in the repressive wake of the revolution. We met weekly at a sauna with two other women in their late seventies. Her English wasn’t fluent but somehow we would find a way to talk, tell our stories and laugh. The loss of her daughter raised one of the main questions in the book: how do we carry on when we lose those closest to us? How do we learn to smile again? Are we ever free from grief?

The last woman is my own grandmother, who became a widow at 19 years of age during the Second World War. She already had one baby girl and my mother, Roberta, was born a month after my granddad, Robert, died. My gran, Nancy, left school at 14, worked in factories most of her life, raised two children and two stepchildren, married a much older man. Gran was my heroine. Ama would have been a little older than Nancy but I think they share a certain stoicism—even if I suspect both would have hated that description. One of the women in the book says: “Women make do.” I don’t want that to sound depressing! It’s a compliment to women of that generation. They got on with life. Gran never left the house without her make-up on. We present our best face to the world. What else can we do?

As for Ama’s background, well, without giving the plot away, I’d gained a small insight into her earlier life through contacts in Nagasaki. Her splendid house in the city is a composite of some of the lovely homes some students lived in. But in the end Ama is her own being and I didn’t want her solely defined by how her Japanese culture would have crafted her. I had a strong visual sense of what she looked like, how she moved and spoke but mostly I felt her pain, her anger, her quiet, determined removal from the world. Ama’s flaws are the flesh on her bones, I hope.

You include Japanese words and their definitions at the start of each chapter. Where are they from? Why did you decide to use them, and how do they relate to the title of the book? What does the book’s title mean to you?

When I moved into my first flat in Nagasaki I found two books left behind by the departing teacher I was replacing. The first one was called An English Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Bates Hoffer and Nobuyuki Honna (1986). Each definition appears in Japanese with an English translation and is sometimes accompanied by fairly crude but delightful drawings. I picked definitions from the book to form most of the chapter headings. For example the book begins with a definition of yasegaman (endurance). It means the combination of yaseru (to become skinny) and gaman-suru (to endure), or to endure until one becomes emaciated. The language seemed exhilarating different, so vivid and visual.

But beyond the delight of the language itself, I wanted the chapter headings to provide a layer of understanding about some of the cultural mores the characters might be influenced by. I aimed to give readers who were not Japanese a shortcut into that world, a code of sorts since many of the tensions experienced by the characters might be internal ones not expressed verbally. For example, take another definition, sasshi. This can be translated as “understanding” or “conjecture” and refers to the idea that direct self-expression is frowned upon, people are expected to guess what others intend to say. By including sasshi, I hoped readers would understand that what is being said might not be what is being felt. The silences may be where the story lies.

The second book is called Nagasaki Peace Trail, compiled by the organization, Mutual Understanding for Peace Nagasaki (MUP). The guidebook provides a history of the city, a walking trail of landmarks affected by August 9, 1945 and a glossary of terms related to the atomic bomb. Seeing the translations of those terrible words—charred bodies, men literally like rags, ruined city—moved me deeply, not just the words themselves, but also the image of a group of people sitting down and wondering: how do we educate people who are not Japanese about the bomb from a Japanese point of view?

I think that drive for communication, the need to find common ground, to reach some “mutual understanding” despite differences in language, culture and geography, is a glorious ambition.

I did toy with book titles that were a lot shorter. It is a mouthful! That’s part of the point. Communication isn’t easy, neither is appreciating another point of view so different from our own, especially if that point of view comes from a person once labeled an “enemy.”

When we meet Ama she has been living in America for years but her English is still poor. This suits her. She doesn’t want to communicate with neighbors; she wants to be cut off by her lack of vocabulary and grammar. If she can’t speak English, she can’t tell her story. Her journey is about learning to converse with the past rather than rejecting it. Can she reach a mutual understanding with people who are no longer alive?

Japanese people might look at the novel and think: “Hmm, so you’ve decided to write a book set during one of the most painful periods of our history from the point of view of a Japanese woman when you don’t speak the language, have not been brought up in the culture and were not alive at the time? Really?” The title is also meant to acknowledge that I am attempting to cross cultures to reach common ground. Clearly I am not a man. I am not Asian. I’m not a soldier. But when I read accounts from Japanese soldiers of those final days of war as they marched, diseased and starving, through stinking jungles and rotting coastlines, I can imagine the suffering. I recall stories of men clinging together in one final embrace as they detonated a hand grenade between them, or soldiers collecting the fingers of fallen comrades so that some part of the dead could be cremated and returned to their families. These men fought against my paternal granddad in Burma, but in those moments of death, I don’t see sides taken, I just see young men dying. I guess that is my attempt at mutual understanding.

**************************************

RECIPES

Castella Cake

20x20cm (approx. 8in. square)

Ingredients:

6 large eggs

200g (7 oz) caster (superfine) sugar

6 tbsp golden syrup

50 ml (3 ½ tbsp) mirin (rice wine)

170 g (6 oz) strong flour

40g (2 2/3 tbsp) demerara (raw) sugar

Preparation:

1. Break eggs into a large bowl.

2. Line cake tin with baking paper.

3. Scatter demerara sugar evenly over the base of the cake tin.

4. Preheat oven to 200°C (around 400°F).

5. Boil water for water bath.

Instructions:

1. Place bowl with eggs in a tray with water (at around 100°F) and whisk eggs for

2 minutes.

2. Remove bowl from water and add sugar, continue to whisk for at least 10 minutes until the batter forms ribbons when lifted.

3. Heat mirin in the microwave for 5 seconds and whisk into the egg mixture.

4. Heat golden syrup in the microwave for 5 seconds until runny and whisk into the egg mixture.

5. Sieve the strong flour into the egg mixture and whisk for 30-40 seconds (no longer or the mixture will not rise when baked) until the flour is completely absorbed.

6. Gently fold the mixture for about a minute to remove air bubbles (this shouldn’t take more than 2 minutes).

7. Pour mixture from a height into the cake tin.

8. Using a chopstick or skewer, draw lines over the surface of the mixture (left,

right, up, down) to remove air bubbles.

9. Place cake tin in oven, and reduce temperature to 170°C (around 340°F) for

10 minutes.

10. Reduce temperature to 140°C (around 285°F) and bake for 75 minutes.

11. Once done, remove cake tin, and drop from a 30cm (½ in.) height onto a chopping board to remove any trapped air.

12. Remove cake from tin immediately and wrap tightly in cling film.

13. Cake is ready to eat, however the flavor is even better after 2–3 days.

1. Place bowl with eggs in a tray with water (at around 100°F) and whisk eggs for

2 minutes.

2. Remove bowl from water and add sugar, continue to whisk for at least 10 minutes until the batter forms ribbons when lifted.

3. Heat mirin in the microwave for 5 seconds and whisk into the egg mixture.

4. Heat golden syrup in the microwave for 5 seconds until runny and whisk into the egg mixture.

5. Sieve the strong flour into the egg mixture and whisk for 30-40 seconds (no longer or the mixture will not rise when baked) until the flour is completely absorbed.

6. Gently fold the mixture for about a minute to remove air bubbles (this shouldn’t take more than 2 minutes).

7. Pour mixture from a height into the cake tin.

8. Using a chopstick or skewer, draw lines over the surface of the mixture (left,

right, up, down) to remove air bubbles.

9. Place cake tin in oven, and reduce temperature to 170°C (around 340°F) for

10 minutes.

10. Reduce temperature to 140°C (around 285°F) and bake for 75 minutes.

11. Once done, remove cake tin, and drop from a 30cm (½ in.) height onto a chopping board to remove any trapped air.

12. Remove cake from tin immediately and wrap tightly in cling film.

13. Cake is ready to eat, however the flavor is even better after 2–3 days.

****************

Okonomiyaki

Serves 2, can be easily multiplied to serve more

*The original recipe uses metric measurements. There are estimated US conversions

in parentheses below, though the metric measurements are more precise.*

in parentheses below, though the metric measurements are more precise.*

Ingredients:

100g (3 ½ oz) unsmoked bacon, cut into bite sized pieces

200g (7 oz) cabbage, finely chopped

110ml (3 ¾ oz) dashi (if you are using dashi powder 2 tsp should be dissolved in 110

ml of warm water)

1 tsp soy sauce

1 tsp mirin (rice wine)

70g (4 ⅔ tbsp) plain flour

30g (2 tbsp) self-rising flour

1 medium egg

100g (3 ½ oz) unsmoked bacon, cut into bite sized pieces

200g (7 oz) cabbage, finely chopped

110ml (3 ¾ oz) dashi (if you are using dashi powder 2 tsp should be dissolved in 110

ml of warm water)

1 tsp soy sauce

1 tsp mirin (rice wine)

70g (4 ⅔ tbsp) plain flour

30g (2 tbsp) self-rising flour

1 medium egg

Toppings:

Tonkatsu sauce

Mayonnaise

Aonori powdered seaweed (optional)

Bonito flakes (optional)

Tonkatsu sauce

Mayonnaise

Aonori powdered seaweed (optional)

Bonito flakes (optional)

Instructions:

1. Combine mirin, flour, soy sauce, dashi and egg in a large mixing bowl.

2. Mix well until all flour is dissolved.

3. Add bacon and cabbage to the bowl and mix in well.

4. Add a little oil to a large frying pan and place on medium heat.

5. Pour pancake-sized portion in to the pan and cook until golden brown.

6. Flip the pancake and continue cooking until opposite side is golden brown.

7. Place on plate and cover with mayonnaise and Tonkatsu sauce and

other toppings.

1. Combine mirin, flour, soy sauce, dashi and egg in a large mixing bowl.

2. Mix well until all flour is dissolved.

3. Add bacon and cabbage to the bowl and mix in well.

4. Add a little oil to a large frying pan and place on medium heat.

5. Pour pancake-sized portion in to the pan and cook until golden brown.

6. Flip the pancake and continue cooking until opposite side is golden brown.

7. Place on plate and cover with mayonnaise and Tonkatsu sauce and

other toppings.

**************************************

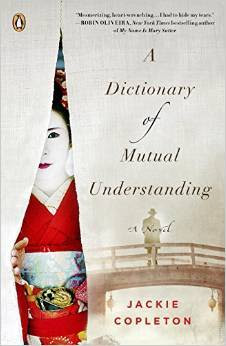

In the tradition of Memoirs of a Geisha and The Piano Teacher, A DICTIONARY OF MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING by Jackie Copleton is a heart-wrenching debut novel set against the 1945 atomic bombing of Nagasaki, rich with intimate betrayals, family secrets, and a shocking love affair. Copleton deftly weaves a narrative spanning decades, moving seamlessly between Philadelphia forty years after World War II, Nagasaki during the war and in the years leading up to it, and the Japanese hostess bars of early 20th century Nagasaki.

When Amaterasu Takahashi opens the door of her Philadelphia home to a badly scarred man claiming to be her grandson, Hideo, she doesn’t believe him. Her grandson and her daughter, Yuko, perished nearly forty years ago during the bombing of Nagasaki. Ama is forced to confront her memories of the years before the war: of the daughter she tried too hard to protect and the love affair that would drive them apart, and even farther back, to the long, sake-pouring nights at a hostess bar where she first learned that a soft heart was a dangerous thing. She must decide whether the man calling himself Hideo is really her long-lost grandson. Once you’ve become adept at lying to others and yourself, can you still recognize the truth? Will Ama allow herself to believe in a miracle?

For many, Hiroshima and Nagasaki are distant place names learned from a history book in a sterile classroom. In A DICTIONARY OF MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING, Jackie Copleton brings to light a rarely examined era, delivering an impassioned story of family, loyalty, and love that allows readers in the Western world to confront the devastating effects of “Fat Man” on the people of Nagasaki—its human toll, and the lasting emotional and cultural impact. In the current nuclear climate this novel serves as an elegant reminder of our shameful history, but also of the vulnerability of survival and the real meaning of peace.

Publisher: Penguin Paperback Original

Format: ebook, paperback. audio

Release Date: December 1, 2015

Buying Links: Amazon* | OmniLit* | Book Depository* | Barnes & Noble | iBooks*

* affiliate links; the blog receives a small commission from purchases made through these links.

The publisher is giving away one print copy to a US reader. The giveaway ends at 11:59PM EDT on November 18th, 2015. No purchase necessary. Void where prohibited. Please read my Giveaway Policy and my Privacy Policy.

Thanks for this captivating and wonderful novel feature and giveaway. The interview was riveting and fascinating. What a life, a history and the idea for this great novel which is memorable and unforgettable. What interests me is the entire book, the settings, the era and the characters. The author explored such an important, meaningful and profound topic and history which is vital. saubleb(at)gmail(dot)com

ReplyDeleteI'm so glad people are enjoying this feature. :)

DeleteWhat a fantastic feature! I normally don't care for non-review features but I really feel like I got a sense of the book and the tone. The blurb and the cover have caught my eye as well and it sounds like this is well worth the read. I love the recipes! I'm especially interested in the cake. Partly because cake is good and partly because I don't think I've really tried any baked Japanese desserts.

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you like the post! Recipes are fun to share and the interview was awesome, too good not to share.

DeleteLove the recipes. Am I brave enough to try them? we'll see. Thanks very much for the insightful interview. I wonder if the author has plans to write more stories featuring Japan or what she wants to do next instead.

ReplyDelete